PTCA using drug-eluting balloons

If the patient remains symptomatic despite drug-based therapy, coronary artery stenosis can be treated in the catheterization laboratory. In cases where restenosis affects a previously treated section, drug-eluting balloons may offer a further treatment option.

What is PTCA using drug-eluting balloons?

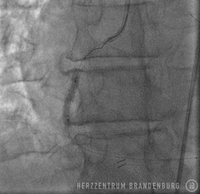

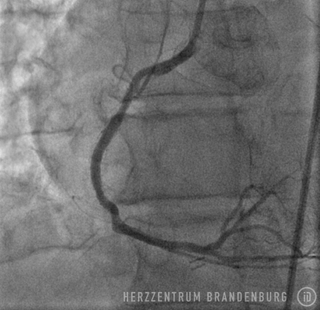

The use of drug-eluting balloons during PTCA constitutes a variation on the standard procedure, which is performed using different materials. The procedure usually starts by advancing a balloon catheter to the site of restenosis. Balloon angioplasty is performed to widen the vessel. As part of the second step of the procedure, a drug-eluting balloon is advanced to the site and then expanded. This establishes close contact between the balloon's surface and the artery wall, allowing for the drugs to be delivered directly to the artery wall.

Historical origins and development

In 1929, the first catheterization of a human heart took place in Eberswalde, in the Federal State of Brandenburg, and was performed by Werner Forssmann, a German urologist. At that time, and for many years to come, the procedure was limited to investigations involving the right side of the heart. During the 1950s, and after undergoing further developments, the technique finally allowed access to be extended to the left side of the heart.

In 1959, Mason Sones performed the first catheterization procedure involving contrast agents, which allowed selective visualization of the coronary arteries using x-ray technology. Over the course of the next few years, cardiac catheterization was mainly used for diagnostic purposes. It was not until the early 1970s that Andreas Grüntzig discovered that balloon catheters could be used in the treatment of stenotic blood vessels. After managing to reduce the size of the balloon catheters used, Grüntzig performed the first-ever balloon angioplasty procedure on a coronary artery in 1977.

The first stent implantation was performed in 1968 by Charles Dotter, who implanted stents into the arteries of dogs. Once the technology had undergone further development, Palmaz et al. implanted the first balloon-expandable stent in 1985, followed by Sigwart et al., who implanted the first self-expanding stent in 1987. Over the next few decades, the technique underwent substantial developments which, on the one hand, focused primarily on efforts to minimize the size of the materials and equipment used, and on the other, on changes in stent design, which included the introduction of stents with drug-eluting coatings.

Despite the use of these new designs and drug-eluting materials, 5-10% of patients develop in-stent restenoses in the years following treatment. It was Scheller et al. who, using a larger group of patients, were able to show for the first time that drug-eluting balloons provide a suitable treatment option for patients with diffuse stenosis.

What conditions are treated with this procedure?

Coronary heart disease with angina pectoris and restenosis of a previously treated section.

What is the purpose of this procedure, and what are the results?

A PTCA procedure is performed in order to treat coronary artery stenosis, and to alleviate the symptoms of angina pectoris associated with physical exertion. Once the degree of narrowing reaches approximately 75%, normal blood supply is impeded during episodes of physical exertion. This leads to the heart receiving insufficient amounts of oxygen, which in most patients will lead to exercise-induced chest pain known as angina pectoris. Treatment of stenosis using balloons and/or stents leads to normal blood flow being restored to a previously narrowed section.

Depending on the nature of any concomitant disease, and the characteristics of the stenosis, treatment to prevent restenoses in the months following treatment may involve bare metal or drug-eluting stents. Depending on the technique used for stent implantation, the type of stent used and the characteristics of the treated section of the artery, between 5-10% of patients will develop in-stent restenosis, even after treatment with drug-eluting stents.

Following standard techniques, a guide wire is used to cross the site of narrowing which, in most cases, will initially be widened using a standard balloon catheter. The balloon catheter is then replaced with a drug-eluting stent containing the drug Paclitaxel, which is advanced into the narrowed section, and inflated for 45-60 seconds. While the balloon remains inflated, the drug is released from its surface and delivered directly to the walls of the artery, where it can produce the desired effects over the next few days. This procedure is suitable in patients with just one single site of in-stent restenosis.

Bypass surgery is usually preferable in patients with restenosis affecting a number of previously treated sites.

Treatment step-by-step

- The patient is positioned on the catheterization table, prepped and draped.

- The wrist, the groin or the inside of the elbow are washed and sterilized.

- Following the application of a local anesthetic, a tiny incision is made in the artery.

- EA catheter is introduced and advanced to the coronary artery.

- The guide wire is used to cross the stenosis inside the coronary artery.

- The guide wire is used to advance a balloon to the site of the stenosis, where it is inflated.

- The balloon is retracted, a drug-eluting balloon is advanced in its place and inflated.

- Balloon and catheter are removed. A pressure bandage may be applied to the entry site, or it may be closed using a wound closure system.

- The patient is kept under observation, and will usually be discharged the day after the procedure.

Web links

Deutsche Herzstiftung (German Heart Foundation)

http://www.herzstiftung.de/

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kardiologie (German Cardiac Society)

http://dgk.org/

PPatientenfassung der Versorgungsleitlinie [Patient version of the treatment guidelines]

http://www.versorgungsleitlinien.de

Sources

- Peterson KL, Nicod P (Hrsg.) Cardiac Catheterization. Methods, Diagnosis, and Therapy. 1st ed. Saunders. Philadelphia, Toronto, Montreal, Sydney, Tokyo. 1997.

- Topol EJ: Textbook of Interventional Cardiology. 5th ed. Saunder, Elsevier. Philadelphia 2008.

- Krakau I: Das Herzkatheterbuch [The Book of Cardiac Catheterization]. Scheller B, Hehrlein C, Bocksch W et al. N Engl J Med. 2006 Nov 16;355(20):2113-24. Thieme Stutgart, New York 1999.

- Scheller B, Hehrlein C, Bocksch W et al. N Engl J Med. 2006 Nov 16;355(20):2113-24.