Recanalization of chronic total occlusion

Up to a third of patients who undergo cardiac catheterization have chronic occlusions (blockages) in the coronary arteries. These occlusions can either be treated using bypass graft surgery performed on an open heart, or they can be opened up using a catheter.

Contact

What is recanalization of chronic total occlusion?

Up to a third of patients who undergo cardiac catheterization have a chronic occlusion affecting one of the coronary arteries. If the occlusion develops slowly, other blood vessels around the heart will form neovascular channels to bypass the blockage, preventing a heart attack from developing. In terms of overall capacity, however, these neovascular networks are inferior to the normal arterial network, and many patients will develop symptoms of angina pectoris upon physical exertion.

If the type and extent of the occlusion allow it, the blockage may be able to be treated using special wires, tiny catheters and balloons. In order to ensure the long-term success of this treatment, all revascularized vessels need to be treated with a drug-eluting stent.

Revascularization restores normal blood flow to the heart. In many patients, treatment completely eliminates all symptoms of angina pectoris.

Historical origins and development

Once cardiac catheterization became recognized as a useful diagnostic tool for patients with heart disease, Andreas Grüntzig, a German-born physician, developed the procedure further, becoming the first person to perform balloon angioplasty in a patient with carotid stenosis.

During the early days of this treatment method, equipment and expertise were understandably scarce. This resulted in a number of early procedures being performed on patients with relatively new vascular occlusions. Over the next few decades, it became gradually accepted across the profession that the term chronic occlusion should only refer to occlusions that had been present for at least three months. The process involved in re-opening vessels that have been occluded for some time is much more complex and time-consuming than the process involved in treating stenoses or acute arterial occlusions.

As a result, the development of new treatment options for the recanalization of chronic occlusions, and the development of new tools by the different manufacturers, went hand in hand. Developments over the years have included major improvements in the design and manufacture of guide wires, which are used to cross the site of occlusion, as well as efforts to minimize the size of both balloons and catheters. The treatment of chronic total occlusions can be divided into two different treatment approaches: Recanalization of an artery can be antegrade (in the normal direction of blood circulation) or retrograde (opposite to the normal direction of blood circulation). With 15-20% of patients not responding to antegrade therapy, the retrograde approach, first described by Surmely et al., made treatment available to a wider range of patients.

What conditions are treated with this procedure?

This treatment is indicated in patients with pre-existing coronary heart disease, chronic total occlusions, and angina pectoris.

What is the purpose of this type of treatment, and what are the results?

If one of the coronary arteries is found to have a chronic total occlusion, initial tests will have to establish whether the affected area of the heart muscle still contains viable tissue. The following tests are used to establish this: ECG, levocardiography (x-ray examination of the left ventricle, using contrast agents), cardiac ultrasound, myocardial scintigraphy and cardiac MRI. If the above tests confirm that the site of the occlusion does not contain any scarring, or is unlikely to contain any scarring, and if the affected patient develops symptoms of angina pectoris upon exertion, recanalization can be attempted. Cardiac catheterization, balloon angioplasty and stent implantation usually follow these tests.

When treatment is used for chronic total occlusions, standard techniques are modified accordingly.

As it is usually necessary to produce images of the blood vessel on both sides of the site of occlusion, and as it is necessary to use the artery's neovascular channels to access the occlusion from the distal end, access has to be made via two arteries. Access can be established using either both radial arteries, the femoral artery, or a combination of the two.

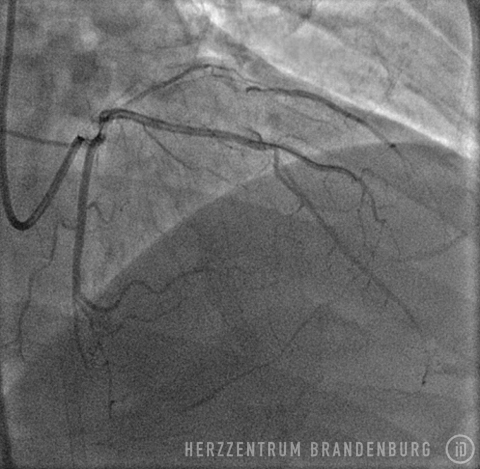

At the start of the procedure, catheters are advanced into both coronary arteries, where a contrast agent is injected, allowing the type and extent of the occlusion to be visualized, as well as calcifications and the degree of arterial tortuosity. In most patients, recanalization is first attempted in the antegrade direction (the normal direction of blood circulation). This involves the use of wires of different strengths and coatings to cross the site of the occlusion. If the site of the occlusion can be crossed, this wire is usually removed using a tiny catheter, and replaced with a standard wire which poses less of a risk. This wire is then used to gradually widen the occluded section using a balloon catheter; in many cases, a drug-eluting stent is implanted following balloon angioplasty, with a balloon catheter being used to ensure that the stent is properly expanded.

If the site of the occlusion cannot be crossed using the antegrade approach (in the direction of the normal blood flow), the procedure can be repeated at a different time using a retrograde approach (from the direction of the neovascular channels). A retrograde procedure requires suitable neovascular channels, as well as a sufficient supply of the required specialist materials. In addition, the center treating the patient must have sufficient experience in performing this type of procedure.

The procedure's effectiveness is down to the fact that within the human body, neovascular networks are less efficient than natural blood vessels at supplying blood to tissues. Re-establishing normal blood supply by enabling the original blood vessels to perform their intended function therefore improves the patient's exercise capacity, ensuring that angina pectoris is either eliminated or only develops once the patient reaches a high level of exertion. Many patients will be able to reduce the amount of medication that would normally be required to support tissue perfusion. As the procedure involves the implantation of stents, however, all patients will require antiplatelet drugs. In addition, patients will require long-term drug-based treatment in order to slow the progression of their vascular disease.

Unless very specific circumstances apply, patients will generally need to undergo repeat cardiac catheterization six months later in order to assess long-term results.

Our Heart Center offers recanalization of the coronary arteries using both the antegrade and retrograde methods. Each patient is assessed individually, and the decision as to the most suitable treatment option is made in close cooperation with both cardiac surgeons and anesthetists. The decision as to whether the patient is more likely to benefit from cardiac catheterization or bypass surgery depends on whether one or several arteries are affected, and whether the surgical risk is significantly increased due to concomitant disease or previous surgery.

The procedures involved in the recanalization of chronic total occlusions

- The patient is positioned on the catheterization table, prepped and draped.

- Wrist and groin are sterilized.

- Following the application of a local anesthetic, tiny incisions are made in two arteries.

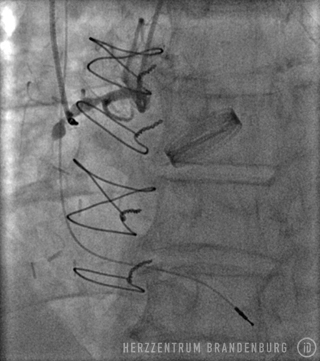

- A guide wire is used to introduce sheaths into the arteries.

- Two catheters are introduced and advanced to the coronary arteries.

- A guide wire and a tiny catheter are used to cross the site of the occlusion.

- The occlusion is gradually widened using a balloon catheter.

- Drug-eluting stents are implanted.

- Balloon and catheter are removed. A pressure bandage may be applied to the entry site, or it may be closed using a wound closure system.

Further information

Deutsche Herzstiftung (German Heart Foundation)

herzstiftung.de

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kardiologie (German Cardiac Society)

dgk.org

Patientenfassung der Versorgungsleitlinie [Patient version of the treatment guidelines]versorgungsleitlinien.de

Suggested reading

Shah PB. Management of coronary chronic total occlusion. Circulation. 2011 Apr 26;123(16):1780-4.

Sources

- Peterson KL, Nicod P (Hrsg.) Cardiac Catheterization. Methods, Diagnosis, and Therapy. 1st ed. Saunders. Philadelphia, Toronto, Montreal, Sydney, Tokyo. 1997.

- Topol EJ (Hrsg): Textbook of Interventional Cardiology. 5th ed. Saunders, Elsevier. Philadelphia 2008.

- Krakau I: Das Herzkatheterbuch. [The Book of Cardiac Catheterization] Thieme Stutgart, New York 1999.

- Ryan TJ. The coronary angiogram and its seminal contributions to cardiovascular medicine over five decades. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2002;113:261-71.